Sunday 23rd August 2020 – Autistic Coding on Stage : Dear Evan Hansen, The View Upstairs and me – #1

Hi everyone!

This is a longer-form piece of analysis of the autistic coding of certain characters in three recent examples of popular musical theatre shows. If that’s not to your interest, there are other pages on the internet ;-). It will be in two or three parts, discussing the context of autistic coding, then apply that to Dear Evan Hansen and The View Upstairs.

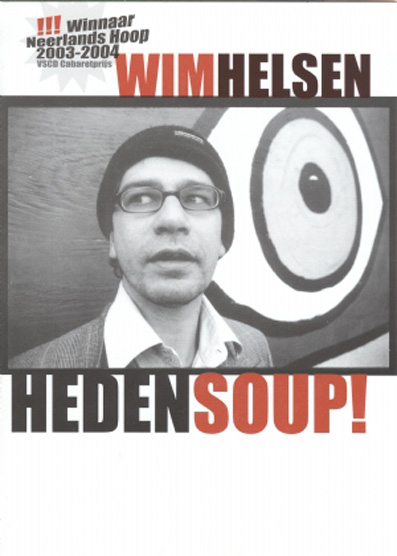

When I was 18, I got in to drama school. I also don’t quite know how that happened. I think it had something to do with an autistic body being on stage despite flaring anxiety being undeniably watchable. I knew that I wanted to be a comedian when I saw Wim Helsen on TV when I was 16. He was playing a character that I can now see had very strong autistic overtones. His physicality was intense and his references seemed to be very important to him but to the audience, he seemed to be unreadable – yet somehow fascinating. People couldn’t keep their eyes off him. This show, Heden Soup! (or: ‘Soup, currently’) constantly played with the audience, daring them to engage with the character on stage. As with much Dutch-language comedy, the audience is addressed directly, though within the confines of a theatre, rather than a comedy club. Helsen’s character, the Soup guy, ticked a lot of boxes when it came to tropes on mental health in theatre.¹ Being on stage, being that weird and actually being liked; Wim Helsen’s character was a revelation. This was different than I had experienced. I had used comedy as a safety mechanism all my life, it was a way of defusing bullies and of cheering up my mum. For my mum’s 38th, my uncle gave her a book of collected comedy monologues that I learned off by heart. He had no idea what he had unleashed. Later that year, I was diagnosed autistic and fought it tooth and nail.

I didn’t believe I could be autistic. I didn’t feel cut off emotionally; I was incredibly empathetic. I wasn’t robotic, my emotional range was huge, I felt things incredibly deeply. The idea that there were certain “wires in my head that didn’t connect up right” made me lose confidence that my brain was even a valid means of interacting with the world around me, rather than inherently broken. I was certainly not happy being a loner – the psychiatrist used the beautiful German word Einzelgänger, I hated the German language for a good few years after that. The idea that I was alone and friendless out of choice was deeply insulting to me. I didn’t choose to be different. I didn’t want to be different. I exhausted myself on a daily basis to be sociable like everyone else and think my way through complex social interactions whilst also not disappointing my father by not being top of the class in every subject. Something had to give and I had violent meltdowns where I would punish, hit and bite myself. I changed to a Steiner school in late 1996, where I was able to function in fits and starts. I still didn’t believe I could be autistic. I was not a robot, I felt other people’s feelings (and those of animals) incredibly deeply, so I just had to batten down the hatches and “act normal”².

As I said before in my blog about radicalisation, while our differences are recognised and often punished (diagnosis or no diagnosis), our capacity for emotional complexity is not recognised in mainstream culture. I got into drama school because standing on a stage, all alone in front of a room of people judging me, was easier than having to be a human being, in school. I had some form of control. For the first time in my life, I felt powerful. I got into drama school by a combination of controlled focus (I constantly expressed just a little too much fascination with everything there, intentionally so) and authenticity that was not in control. I now realise I also got in because of my voice (I have perfect pitch and a talent for impressions). Getting in meant I now had a purpose: I needed to succeed. I needed to battle and I needed to be in full control of everything: how I looked, how I spoke, how I interacted with people. This was my one shot. Don’t fuck it up.

Before the year started, already out of my depth, I read everything I could about theatre, acting and Dutch comedy. Before the year even began, I took part in a stand-up comedy masterclass. I was a mess. I didn’t even know where to start. I was awkward on stage, had no idea what I was doing. My material was undercooked, with little to no potential. I was roundly ridiculed in front of my peers, about forty audience members and two professional stand-up comedians who were TV mainstays. I just had to suck it up. It was a huge blow to my confidence, already strained after trying to assert control of my entire being that summer.

A few days after, during the introductory weekend, the school played a prank on the new intake – that they were actually a cult of some sort. All new students were concerned and discussed whether they should stay. I thought: “if this is what it takes, I’ll do it.” I didn’t just fall for the joke, I bought in. I knew I wanted this more than I wanted dignity as a person. Showing how much I wanted it, however, only served to push people further away. My anxiety was peaking, I barely slept, drank consistently. I was out of control. I had no ideas, my brain flatlined when I was asked a question or to make a short performance piece. I didn’t know how to think my way into this world, where people worked from their instincts. I thought this place would allow me to work on what I was meant to do, with people I could be friends with. I was mocked, ridiculed and pitied instead. I caught the flu and couldn’t make the first week’s lessons, my classmates were under the impression that I’d quit. But I wouldn’t quit. Quitting is what failures did, what my father did. I don’t quit when things are tough.

My first week of classes, I was asked to enter the stage. I then had to leave again, my “energy wasn’t there”. I had to enter again, and again, and again. I was told that I had “a fourth wall” in front of me. I was apparently pretending that the room wasn’t there – I was not, I was painfully aware of them. The teacher – who was also the director of the school – told me I needed to just keep on doing it, in front of my peers, who looked at me with a mixture of pity and resentment. I started crying. The teacher, not knowing what was happening but wanting to make me feel better, said “ok, maybe you can work with that.” I was totally burnt out. That was week one. I was there for two painful years.

I tried to play the game, both in interactions with my fellow students, the staff and the directorship. I was totally out of my depth and felt I’d fallen at the first hurdle. My parents were exasperated with me. I was clearly suffering, so why was I so bought in to a career I could never have and particularly this school? Because I thought it was my only chance at life. If not being neurotypical, then using my idiosyncrasies and be valued for them them, rather than just be ridiculed by people in the street for walking in a weird way or having a stupid voice. I would be paid well and I would be well-known enough to be hassled in the street for positive, rather than just negative reasons. At least there would be something to undo the daily difficulties of living. I’d suffered enough in my life. Now it was time to cash in, both literally and metaphorically. At least I wouldn’t be my father.

I was told that I was, as an stage personality, low-status. They meant that my shoulders were hunched, my voice nasal, and I expressed a variety of “unnecessary” physical movement expressing uncertainty and anxiety. I flapped my hands, my eyes didn’t always focus on the person I was speaking to, I jumped around sometimes. I didn’t know, but a low-status physicality is played with autistic traits. Without intending to, hundreds of years of theatrical coding have situated the traits of an autistic body – whether in a state of distress or joy – as someone who cannot possibly be powerful. When you play Lear, the point is to shift his body language from very at ease and calm to a shivering, shaking wreck. You turn him from neurotypical into neurodivergent and the audience knows to pity and fear him. Rather than just knowingly imposing autistic traits onto a character (see last week’s blog and the Jessica Kellgren-Fozard video linked in it), this also is autistic coding. The use of autistic bodily tics and movement to guide an audience’s emotional response against a character is widespread across the history of theatre.

To be sure, none of these traits are inherently autistic. There is nothing inherently autistic about flapping your hands – most people in serious distress have tics such as these, even because of boredom. But these movements are used by others to categorise and disempower us in particular. Furthermore, they are imposed upon characters that express divergent thinking styles, sensory sensitivity/insensitivity and who are, inevitably, disempowered and made weak. It is the combination of those character traits, that physicality and the way an audience is guided to treat them that makes autistic coding highly problematic and empowers those who seek to disempower us. An actually autistic body with an actually autistic mind? On a stage? That’s heresy. Or at least it was in the mid-2000s.

An example from my own life came further into my first year, at a Commedia dell’Arte mask-workshop, I played the Harlequin in the context of a TV game show. I won a point, but I asked the quizmaster to give my point to the other performer onstage. The teacher stopped the improvisation and said: “No. Just, no.” When reviewing the task, I later said “Yeah, what was I thinking.” But I knew exactly what I was thinking: I was playing a low-status character and I showed kindness, a low-status action. But in doing so, I broke a fundamental rule of improvised theatre: to seek conflict, not resolution. That was a jump for someone who’d spent his entire life seeking resolutions to problems others had with him, because of who he was. I am also pretty sure that if anyone else had broken that rule the exact same way would have been praised. Others broke similar rules, stepping onto other people’s punchlines and subverting expectations, with great effect and rapturous laughter, confidently or not. It was yet another example of: “it’s not what you do Jorik, it’s you doing it, that’s the problem.”

I found it very difficult to not take everything that was said in that place absolutely personal. I tried to keep myself safe initially, but I was asked to be “more authentic”. When I was, it “wasn’t right”. I worked even harder off-stage than I did on. But the frustration that staff and students felt towards me went right in. I felt the worst impostor-syndrome I’d ever experienced. The first six months were brutal anxiety. Then, after working harder on a presentation than I’d ever worked on anything in my life, I was mocked by family because “it wasn’t funny, why can’t it just be funny” and by staff and students who said “I just didn’t get it.” Nobody did. I was utterly depressed. I felt that I would be a failure, just like my father. All because I couldn’t hide who I truly was.

When I went to drama school, I was trying to do comedy. But many of my routines – though in structure and subject matter the same as others in my school – were taken literally. Rather than me not possessing the capacity, I was not allowed irony and sarcasm. Therefore I was heavily criticised for work that others got high praise for.³ In my second year, I played a deliberately low-status character, explicitly lovable and sweet. Then I played a song, in character, where he sings about his ideal woman – who would just work efficiently. I was given a warning by the staff. It was misogynist and unacceptable. After, I wouldn’t be allowed to write my own material, but had to focus on music. The point is, they were right. It was unacceptable (Twitter, if you’re there, please feel free to cancel me retroactively). But others in the higher years did similar material to mine, in well-rewarded strides into edgy, “dangerous” territory. But not me, I was punished. I was asked to leave the school at the end of my second year (though I had not progressed beyond the preparatory year at all), with nothing beyond that.⁴

So why had I even got there? I thought it was because of things I could do. Because I could perform and write funny things. It wasn’t. Simply because of the combination of how big my body was (I’m 6”4’) and how lowly my autistic flaps and ticks and shakes were, I was interesting to look at. It was a contradiction that had very little to do with my skills. I thought the opposite: I thought a school was where you go to learn and work on a set of skills. I was constantly asked to be more authentic. The thing that made me interesting on a stage was because of my authentic self, as dangerous as it was for me to show that self. Yet what they meant by that authenticity was never clearly defined. It certainly wasn’t my authentic self. There’s an odd dichotomy between what makes an actor playing an autistic-like character interesting, but an actually autistic person on a stage awkward; unpleasant to look at. The audience doesn’t want to see pain, real pain. They want to see a simulacrum of that pain. The real thing is too much. Robin Williams talked about the idea on his Inside the Actor’s Studio from 2000. Stand-up tragedy isn’t popular – no-one will pay to see someone genuinely suffer on stage. Those first few weeks at drama school told me two conflicting things: they wanted to see more authenticity, but when I showed that authenticity, it wasn’t the right authenticity. They wanted something I could never provide. Because what they saw was what they got, and they couldn’t understand it.

Sexuality was a further complication. I wanted to start coming out when I went to drama school, but the homophobic atmosphere between my male school peers pushed me right back in. The widely-shared idea that musical theatre is an inherently ‘gay’ form of theatre was highly current in Holland in the mid-2000s. There were no out queer people in either the students or staff in my first year at drama school. It was just as homophobic as the world I came out of, if not more. I therefore pushed away from musical theatre, even though I’d always wanted to do it⁵. My voice worked very well for it, too. So that was just another mask to keep on. Not so much a straight mask, but a mask that was desperately non-sexual. Unfortunately, straight people can’t resist trying to tear off that mask, including staff. I therefore also had to perform away my sexuality that entire year.

To be clear, being autistic is not the same as being queer, but as someone who is both, I can see the way they interlink.⁶ Being autistic is an innate difference which challenges the neuronormative model. Simply being in the world can irritate people. I have had many people shout at me and even assault me for simply existing in a room, even while I was masking. Being queer is not just about sex. It’s actually a form of engaging with a world that doesn’t like you for being what you are. Rupaul’s Drag Race, at its best, is showing how people who are shaped by their difference and how the world interacts with them because of it; create beautiful and meaningful art and through it, achieve dignity. Chi Chi DeVayne’s top 6 Lip Sync was so meaningful partly because how dignified she was in a song that, if you look at the lyrics, is about her woman shedding all her dignity and defence mechanisms to keep her man.⁷

Dignity is something that an audience gives to a performer, not the other way around. The same happens in society. Privilege theory helps here, but dignity is one that is particular to neurodiverse people, I believe. Because Black young people are still given dignity by their peers and families, even if society is intent on taking it away. One of the most touching things I saw was in London, in 2011, waiting for a train. A Black man was on the platform, looking exhausted and a little unwell. Then a station staff member went up to him, addressing him as Brother and asking how he was. They clearly didn’t know each other, but this man’s voice was full of kindness, as if he was his grandmother seeing her grandson come home with a black eye. I was really touched by that, as much as I knew I would never be addressed by a stranger in that way⁸.

A low-status character is not given dignity, that’s the point. They don’t deserve it. Their body is saying, in all of its “unnecessary” movement: dehumanise me. I am not worthy to be listened to. I am a rude mechanical, I am Zanni, I am only here while you wait for actually important people to come back. In that sense, the Soup Guy challenges that. The quietness in the performance, despite the constant danger emanating from the character, endears him to the room, despite his intensity.

The other way that autistic bodies can be onstage – particularly male bodies – is as a villain. Autistic low status is relatively harmless in its weirdness, but autistic high status is frightening. Because of the way neurotypical audiences struggle to access our minds and wide cultural misunderstandings both of autism and antisocial personality disorders (see last week’s blog) autistically-coded characters are easily cast as immoral, selfish, even murderous monsters. I was not long in drama school when my view of myself as inherently shifty was strengthened by the director saying: “You’re a clever boy – a crazy boy. There’s a danger there.” The danger was me. I made people feel unsafe. My intelligence was frightening. I know from friends who were mainly cast as villains, the audience is steered to want the destruction of these characters, because of what they are. The essence here is the same as the trope of the Gay Villain – we are frightening because we are different. My intelligence was something that should be feared. Here we find ourselves again at the dichotomy of pity and fear.

Not every performance is as subtle as Wim Helsen’s. Dear Evan Hansen and The View Upstairs are recent musicals that I saw in 2019. I watched Dear Evan Hansen on youtube, as I wanted to see Ben Platt’s Evan and The View Upstairs live, in the Soho Theatre in August 2019 with my autistic friend Chris. I will also make reference to Spring Awakening, both its 2015 Deaf West version and the 2006 original, and Simon Stevens’ Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. I chose musical theatre, partly because I love it and partly because musical theatre has to play with broad characterisations in order to get a character to sing to the room without the audience losing faith in the narrative when the fourth wall gets put back up. Each of these shows contains autistically-coded characters, who strive and fail to achieve dignity and, in the end, the audience is set against them. Their need for dignity in the first place is problematised. They should just have stayed in their lane.

That’s the end of part one. I will dive deeper into the shows I’m going to discuss next week. Expect thoroughgoing shade and pedantic analysis. I know you’ll be here for it. Love you all.

Footnotes:

¹Ten years later, I wrote a paper on representations of mental illness in 20th century drama during my MA, let me know if you’re interested. TLDR: they’re bad). Wim Helsen, as far as I know, is neurotypical, though I have no access to interviews in Flemish newspapers that discuss neurodiversity. I have not watched or read Heden Soup! in decades though. I can’t give a critical overview of a show I haven’t seen since 2005.

² The Dutch expression “doe eens normaal” – an imperative to act normal, like everyone else, is still particularly painful to me. It says: Don’t be what you are, either be someone else or go away. People who’ve verbally and physically assaulted me did so because I wasn’t and said so at the time and afterwards.

³ This is an example of the double-empathy problem, as written about by Dr Damian Milton. Look for A Mismatch of Salience online. Buy it from the original publisher, as they pay their taxes.

⁴ Luckily, theatre group De Bloeiende Maagden took me under their wing and I toured the Netherlands for nine months, performing in their new show Donky God de la Mancha.

⁵My mum bought me a three CD box with “The Greatest Musical Theatre Hits” for my birthday in 1997, to the great irritation of my father.

⁶ For more information, see here: https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/neuroqueer-an-introduction/

⁷ See here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hJOmm5fck-0 Season 8 was my first season. I loved her Chi Chi’s story, her rise from poverty in Louisiana to top 4 and All Stars. RIP Chi Chi DeVayne. Hero and Goddess.

⁸ Happily, I turned out to be wrong. The kindness of strangers who are either ND themselves or family/friends of autistics is real and just as profound. During public meltdowns I have also been supported by queer people and people of colour with no connection to autism – at least that they knew of. But they saw someone in trouble and stepped in with kindness.

One Reply to “Sunday 23rd August 2020 – Autistic Coding on Stage : Dear Evan Hansen, The View Upstairs and me – #1”

Comments are closed.

Once again Jorik this is a fascinating blog and although at times painful to read, it absolutely captures the reality of the situation. I love reading your blogs by the way.